Living and Dying Under Dobbs, vol. 6 (no audio). Scroll down to read the stories.

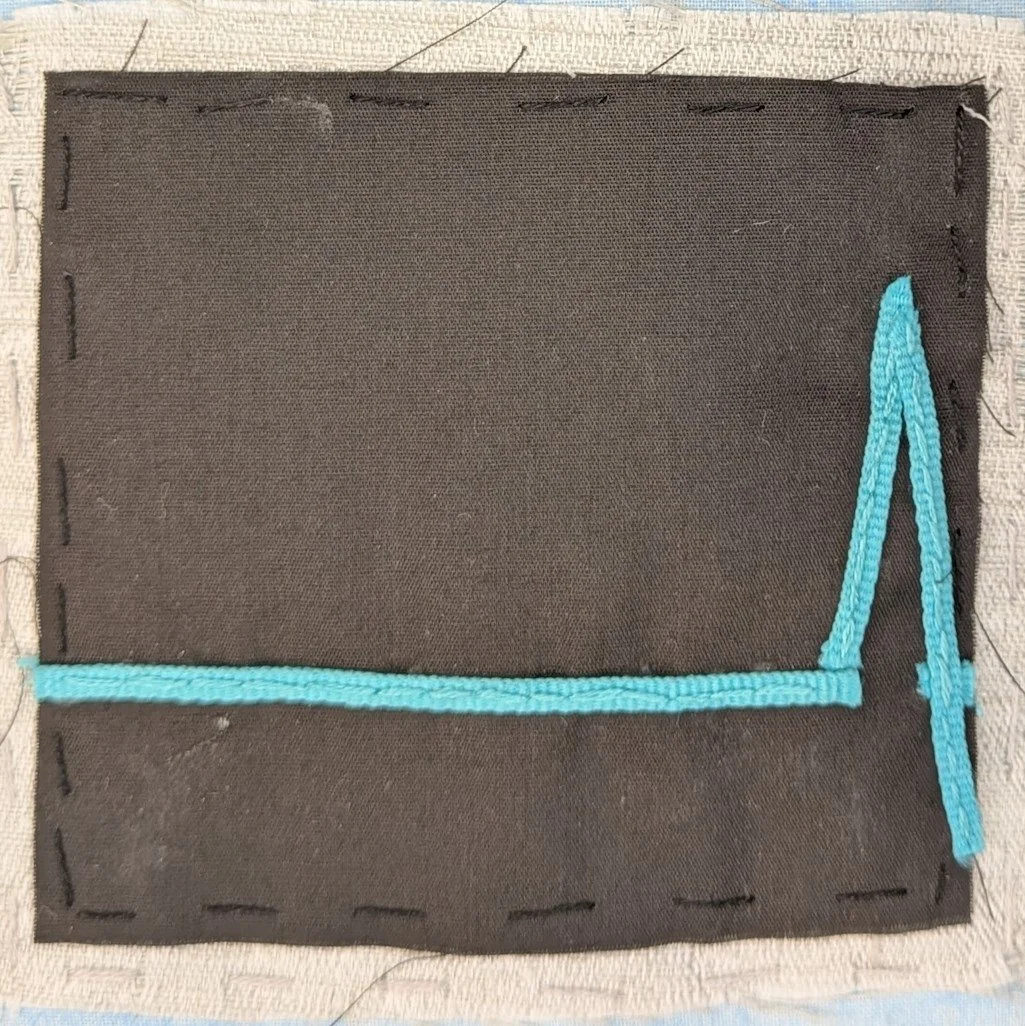

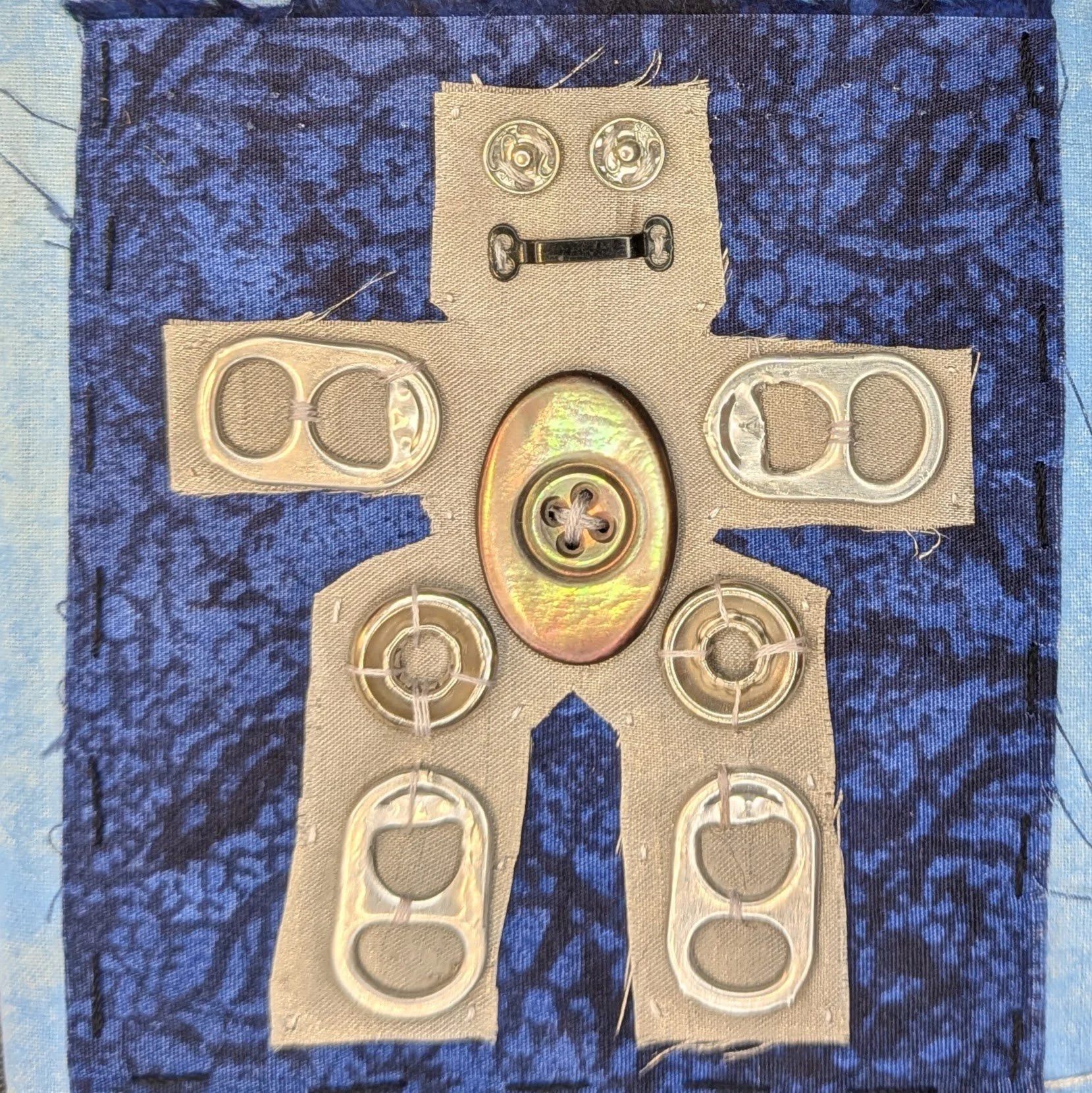

Volume 6 of the ongoing textile book.

Scroll down to read the stories.

In Kansas, the Women’s Right to Know Act is now being challenged in court. The law mandates that abortion providers require a 24-hour waiting period for patients to complete consent forms with specific colors and typefaces and that clinics display large signs with state-scripted language saying that a 20-week fetus can feel pain, which is disputed. Lynette Rainey, staff member from 2018 to 2023 at a clinic party to the lawsuit, said they used a kitchen timer to track the 30 minutes patients are required to wait between their initial meeting with a doctor and receiving an abortion. Lynette said a woman pregnant by rape drove from Texas but brought the wrong consent forms. She had to require that the woman again wait at least 24 hours to submit the right ones. By the time the woman returned, her pregnancy was too far advanced for her to receive an abortion. “It was devastating,” Lynette said. “It was so hard to be the person that says, ‘Hey, I know you’ve got a lot going on, but, sorry, we can’t help you.’”

At 18 weeks of pregnancy, Kayla Moore learned that her cervix had begun to dilate and the baby’s foot was emerging. During a doctor’s attempt to stitch the cervix closed, the amniotic sac was accidentally punctured. Before Tennessee’s abortion ban took effect, doctors would have induced labor to prevent infection that could threaten Kayla’s life, but now they had to wait for her condition to deteriorate. “It was a ticking time bomb” Kayla said. “I was just sitting there waiting for something terrible to happen.” She was told that she and the medical team could be charged with murder if they did anything to hasten labor. When Kayla began to hemorrhage from a placental abruption, doctors induced labor and her daughter was stillborn. Kayla, who has a blood-clotting disorder, lost over 5 cups of blood and was on bed rest for weeks. She believes that “Someone who has no medical training should not be deciding when my life is in danger. . . . I do not care which side of [politics] you are on, no one should be in the situation I was just in.”

Elisabeth Weber of South Carolina was told at six weeks of pregnancy that she was miscarrying and sent home. Because she was suffering from hyperemesis gravidarum, as in her previous pregnancies, she was bedridden with extreme nausea, so four weeks later she returned to the ER. Although there was no fetal heartbeat, staff again sent Elisabeth home telling her to wait two more weeks and return if she began to hemorrhage or show signs of infection. A staff member suspiciously asked if the pregnancy was “wanted.” Elisabeth said, “`My baby is dead. Every doctor I’ve talked to knows my baby is dead. My baby is not going to magically get a heartbeat.’” After Elisabeth posted a Tik Tok that went viral, a patient advocate called to suggest she go to a different hospital, where she learned she had an infection. Staff sent her home with Oxycodone. After the two weeks ended, Elisabeth received care and could grieve her son.

In Georgia, Kaycee Maruscak learned in her second trimester that her fetus showed no sign of cardiac activity. Doctors would not treat her and gave her a list of what she described as abortion clinics. After several days, when she began to show signs of infection, she went to an ER and learned that she had placenta previa, but doctors sent her home, saying she should come back if she was hemorrhaging. Finally, after carrying her dead daughter Sawyer for several more days, Kaycee found a doctor in Atlanta willing to treat her. In Sawyer’s memory, Kaycee and her husband have planted a garden where they have scattered her ashes. Kaycee says she wants to challenge the laws that prevent doctors from providing treatment to women in her situation. ‘I’m going to fight against this,’ Kaycee says. `People need to hear this story.’”

Nicole Miller and Kate Campbell are two of the six pregnant women airlifted out of state in 2024 when Idaho’s abortion ban prevented doctors from treating them. When Nicole began to hemorrhage at 20 weeks of pregnancy, her doctor said he couldn’t risk his 20-year career to treat her, so she was airlifted to Utah. Also at 20 weeks, Kate went into premature labor and learned that to preserve her future fertility and possibly her life, her doctors recommended that she deliver her son, Remy, and put her on a plane. Later, when Kate found that lawmakers would not listen to her story, and in memory of Remy, she and her husband joined Idahoans United for Women and Families, which is gathering signatures to put the Reproductive Freedom and Privacy Act on the Idaho ballot in 2026. Meanwhile, the number of ob-gyns practicing in Idaho decreased by 35 percent between August 2022 and December 2024.

Four months into her second pregnancy, Kayla Smith learned that the left side of the baby’s heart had barely formed and was irreparable. Dr. Kylie Cooper couldn’t predict whether the baby would suffer after birth if Kayla attempted to complete the pregnancy. Kayla was also at high risk of potentially life-threatening pre-eclampsia, but Idaho’s abortion ban left Dr. Cooper unable to say how sick Kayla would have to be for doctors to save her. Kayla and her husband ultimately decided to drive to Seattle to terminate the pregnancy. Dr. Smith described feeling what researchers call the “moral distress” felt by medical providers across the country as abortion bans prevent them from giving the care they believe is right. In one study of health care workers who care for pregnant patients in abortion ban states, 96% said they felt “moral distress that ranged from “uncomfortable” to “intense” to “worst possible.”” In another study, OBGYN residents reported that abortion bans made them feel like “puppets,” a “hypocrite,” or a “robot of the State.”

Sources

Lynette Rainey.

“Kansas navigates post-Dobbs world with state abortion restrictions in limbo.” Kansas Reflector. Oct. 23, 2025.

Kayla Moore.

“An Arkansas mother’s near-death experience with ‘pro-life’ abortion ban.” Arkansas Times. Nov. 4, 2024. (Note: although Kayla is from Arkansas, her experience happened in Tennessee.)

Elisabeth Weber.

“Woman Forced to Carry Fetus for Weeks Despite No Heartbeat: 'Your Womb Becomes a Tomb.’” People. May 6, 2025.

Kaycee Maruscak.

“Abortion-rights, anti-abortion advocates mark three years of Georgia ban.” WABE. July 22, 2025.

Nicole Miller and Kate Campbell.

“She Needed an Emergency Abortion. Doctors in Idaho Put Her on a Plane.” New York Times. June 28, 2024.

“‘That’s Something That You Won’t Recover From as a Doctor.’” The Atlantic. Sept. 12, 2024.

“On the worst day of our lives, Idaho politicians made it harder.” Idaho Capital Sun. Nov. 18, 2025.

“Idaho's biggest hospital says emergency flights for pregnant patients up sharply.” NPR. April 26, 2024.

Kayla Smith and Dr. Kylie Cooper.

“‘That’s Something That You Won’t Recover From as a Doctor.’” The Atlantic. Sept. 12, 2024.